A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to be in Philadelphia in advance of the nation's birthday. For me it was a time of solemn reflection and pent-up excitement, following in the footsteps of John Adams to the Continental Congress. Although the weather by Las Vegas standards was mild, I felt it eerily appropriate- 93 with 50% humidity, and I noted with some smirk of satisfaction that I was the only one excited by the realism attending to our visit as we stood in a snaking line in the afternoon sun.

John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail of how he thought that Americans would look back on Independence Day as the 2nd of July. On that very night, at a birthday party for my cousin, I told my uncle the story, as I previously recounted on this blog.

On July 2, 1776, Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, signed only by Charles Thompson (the secretary of Congress) and John Hancock (the presiding officer). Two days later Congress approved the revised version and ordered it to be printed and distributed to the states and military officers. Given the high number of absent members and their desire to keep the declaration relatively secret, seeing as how the signatories thereof were committing an act of treason, they tried to hush it up as much as possible. Most of the opponents to independence abstained from the vote, and some never signed it. Adams had been its most ardent proponent.

Interestingly, the pomp and circumstance that many Americans presume took place on July 4, 1776, actually occurred days to weeks afterwards. Despite efforts to keep independence secret with a large British contingent not too far away in New York City, the Philadelphia Evening Post published the Declaration's full text in its July 6 newspaper.

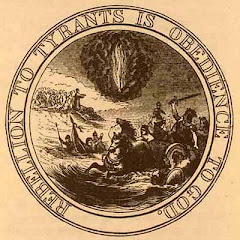

As copies spread, the Declaration of Independence would be read at town meetings and religious services. In response, Americans lit bonfires, fired guns, rang bells, and removed symbols of the British monarchy.

The following year, no member of Congress thought about commemorating the adoption of the Declaration of Independence until July 3 - one day too late. So the first organized elaborate celebration of independence occurred the following day: July 4, 1777, in Philadelphia. Ships in the harbor were decked in the nation's colors. Cannons rained 13-gun salutes in honor of each state.

Fireworks did not become staples of July 4 celebrations until after 1816, when Americans began producing their own explosives, ablating the need to purchase them from abroad.

No comments:

Post a Comment